History of Zenica

Zeničko Polje, dominated by the Bosna River and bounded by the northern Vranduk Gorge and the southern Lašva Gorge, holds a central geographical position in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The city of Zenica is situated at the heart of this field, irresistibly resembling the precious center of the visual sense – the pupil (zjenica in Bosnian), which, according to one tradition, is how the city got its name. With an average altitude of around 350 meters, hilly massifs, and three rivers, with the Bosna River being the largest, Zenica possesses fantastic natural features for a pleasant life for its inhabitants.

The area of Zenica and its immediate surroundings is rich in numerous material evidence showcasing the continuity of civilizations, cultures, and historical events, with the oldest artifacts dating back to the period from 3000 to 2000 BC found at sites like Drivuša and Gradišća. Subsequent discoveries belong to the Bronze Age, found in Orahovički Potok near Nemila, Gračanica, Ravne, and other places, where metal axes, arrows, ornamental fibulas, and remnants of ceramic materials were found. Illyrian tribes, appearing at the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age (6th-5th century BC), constructed a specific type of defensive settlement called ‘gradina’ (hillfort). Indirect evidence from toponymy, such as the toponym ‘gradina’ retained to this day in the names of some settlements like Gradac, Gradišće, and Gračanica, helps to resolve the dilemma about the presence of the Illyrian Desitiate tribe in the Zenica region.

By the end of the 3rd century BC, the Romans began conquering the territory of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, where they would rule during the first four centuries of the new era. This brought about many social and cultural changes, although life continued in numerous Illyrian ‘gradinas.’ The most significant archaeological site from the Roman period is the excavated foundations of an early Christian basilica in the settlement of Bilimišće. This basilica is particularly interesting and noteworthy for several reasons, primarily because only two similar basilicas are known in the European region based on their description. Archaeological finds from this period have also been discovered in the settlements of Odmut, Putovići, and Tišina, with the most interesting being epigraphic inscriptions. These inscriptions led archaeologists to search for the important Roman municipium of Bistua Nova precisely in Zenica.

In the territory of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, the greatest uprising against the Romans was recorded, the renowned Batonian Uprising (6-9 AD), during which Arduba was mentioned, often associated with today’s Vranduk.

The early Middle Ages in the entire territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina are shrouded in darkness, but it is assumed that barbarian invasions destroyed much of the ancient heritage, including the basilica in Bilimišće, believed to be the seat of the Bistua Nova bishopric. During this period, various peoples such as the Goths, Avars, and Slavs passed through Bosnia and Herzegovina. After their invasions, it took several centuries to form the first Slavic states, including Bosnia. The core of Bosnia was precisely in the Sarajevo-Zenica valley.In the Middle Ages, the Zenica region appears in historical sources under the names Bored or Brod, related to a significant river crossing over the Bosna River.

An event that marked the early medieval history of Zenica and Bosnia and Herzegovina was undoubtedly the Bilino Polje Abjuration by Ban Kulin. During the reign of the founder of a strong and independent Bosnian state, Ban Kulin (1180 – 1203), a faith associated with a similar heretical (dualistic) movement in the eastern Balkan Peninsula emerged in medieval Bosnia. Under pressure from the Catholic Church, particularly the Pope and the Hungarian king, Bosnian Ban Kulin, in the presence of the Pope’s envoy Cardinal Ioannes Casamarisa, Archbishop Bernard of Split, and the Dubrovnik deacon Marin, proclaimed the Bilino Polje Declaration on April 8, 1203, renouncing the Bogomil teaching.

From the period of Ban Kulin’s rule, we have the so-called Gradiša’s Grand Judge Stone, found in the settlement of Podbrežje, representing the first significant confirmation of the existence of the judiciary in medieval Bosnia. In the late Middle Ages, we have the first mention of Zenica by this name in a document of the Republic of Dubrovnik from March 20, 1436, related to the incursion of the Turkish duke Barak around Podvisoki and Zenica. Also from this period is the legend of the escape of the last Bosnian queen, Katarina Kotromanić – Kosača, from Vranduk, during which she allegedly said, ‘Osta moja Zenica’ (My Zenica remains), which represents another legend about the origin of the name of the city Zenica.

To retain the recently conquered territories threatened by the Hungarians, the Ottomans resorted to a unique measure in the history of their lands – the establishment of the Kingdom of Bosnia, stretching from Lašva in the south to the areas of Jajce and Srebrenica banovina in the north. The seat of this short-lived kingdom, abolished in 1476, was in Vranduk.

With the fall of Bosnia under Ottoman rule in 1463, Zenica lost its significance as it remained outside the main communication routes, although according to one source from the late 17th century, it had about 330 houses at that time, placing it among the medium-sized Bosnian cities. The Ottomans established the Brod district in Zenica and later the Vranduk Captaincy. Religious and economic structures were built, and by the 17th century, Zenica had fully developed into a town. However, in 1697, during the campaign of the Habsburg prince Eugene of Savoy, Zenica was completely burned down (according to tradition, only three houses survived). A significant number of prominent citizens of Zenica were killed, and the Catholic population of Zenica left the city along with the prince. Zenica took a long time to recover from this blow.

In the 18th century, Croats from Dalmatia and Sephardic Jews started to settle in Zenica.

Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin held in 1878, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was given the mandate to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina, which soon faced armed resistance from the occupying forces. Zenica, specifically the house of Hadži-Mazić, is considered to be the place where representatives of the Ottoman authorities in the Bosnian vilayet, Hafiz-pasha, and the commander of the Austro-Hungarian occupying forces, General Filipović, negotiated the terms for ending the conflict. During the four decades of Austro-Hungarian rule, Zenica underwent significant changes in appearance, size, and functions, primarily influenced by the radical changes in the economic development of the city.

The most significant event for Zenica’s further development was the construction of the narrow-gauge railway from Bosanski Brod to Zenica in July 1879 and then from Zenica to Sarajevo in 1882. Based on thorough geological research confirming the existence of large reserves of high-quality coal in the Zenica area, the territorial administration for Bosnia and Herzegovina opened the Zenica Coal Mine in May 1880, the first coal mine in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Foreign private capital was invested in Zenica, and the most significant enterprise established with private capital was the Packaging Paper Factory, opened in 1885 by Viennese industrialist Eduard Musli. However, the largest and most significant economic venture during Austro-Hungarian rule was the establishment of the Ironworks in 1892, which left a mark on the city’s industrial and urban development.

Another symbol of Zenica was undoubtedly the Central Penitentiary for Bosnia and Herzegovina (later the Territorial Penitentiary), which was constructed in stages between 1886 and 1904. In 1906, the penitentiary housed over a thousand prisoners, and the so-called ‘progressive Irish system’ of serving sentences was implemented, where prisoners were engaged in useful occupations during their sentence.

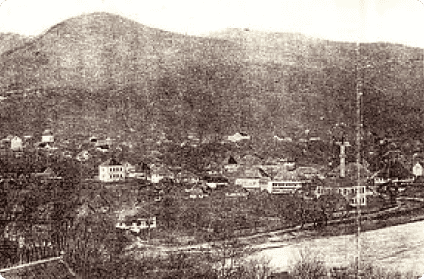

During this period in Zenica, besides industrial facilities, new technical discoveries were introduced that further enhanced its image as a modern European city. The first of such discoveries was the introduction of telephones in 1904, followed by the construction of a modern water supply system, significantly improving hygiene and sanitation conditions. In 1908, an electric power plant was built in Zenica, allowing the introduction of electric street lighting. The construction of industrial facilities and the adoption of modern discoveries led to a rapid increase in the city’s population. According to the census in 1879, Zenica had 438 houses and around 2,000 inhabitants. By 1895, the population had doubled, and according to the third census, there were about 4,200 inhabitants and 765 houses in Zenica. In the last census conducted by the Austro-Hungarian administration in 1910, Zenica had over 7,000 inhabitants and about 1,000 houses. From 1879 to 1910, Zenica experienced a population growth of 391%, indicating a growth greater than natural increase.

The majority of Zenica’s population were Muslims, numbering around 1,700 in 1879 and increasing to about 3,000 in 1910. Catholics numbered around 100 in 1879 and increased to approximately 2,800 in 1910. There were around 200 Orthodox Christians in 1879 and about 1,000 in 1910. The number of Jews also increased from 50 in 1879 to nearly 300. It’s worth noting that Zenica was home to many people from other parts of the Monarchy, particularly from Austria, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, but determining their exact numbers is challenging.

During Austro-Hungarian rule, state schools were established in Zenica, the first in 1885 and the second in 1910. Confessional schools were also present, one each for Catholics and Orthodox Christians, as well as three mektebs (Islamic elementary schools), a medresa (higher Islamic school), and a ruždija (Quran school). Muhamed Seid Serdarević, a mualim in the Sultan-Ahmed Medresa in Zenica, played a significant role in advocating for educational reforms, including teaching in the local language and modernizing the curriculum. Students of both genders attended the classes.

Cultural societies were established in Zenica during this time, organized on a strictly national-confessional basis, such as the Croatian Singing Society, Zvečaj, and Czech Beseda, among others. Concurrently, general-interest societies like firefighting, hunting, and mountaineering were also founded. In 1910, Zenica saw the opening of its first cinema, named Helios, elevating the city’s cultural scene to a new level.

Yugoslavia

After World War I, the Kingdom of SHS was formed, which in 1929 became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, incorporating Bosnia and Herzegovina. Politically, economically, and socially, the life of Bosnia and Herzegovina, including Zenica, from 1918 to 1941, was in a phase of stagnation. However, the situation started to change slightly just before the outbreak of World War II, with certain investments being made in the Zenica Ironworks, which became the largest enterprise in the country with over 4,000 workers. During this period, new cultural and educational societies, Sokol organizations, newspapers, weekly and monthly publications, and political magazines were established in Zenica. Domestic intellectuals, educated abroad, began to emerge and contribute to Zenica’s cultural scene. Notable figures include Derviš Imamović, who was involved in photography, poetry, prose, and drama, and was an editor of the literary magazine “Zeničanin” initiated by the poet Jakov Ozmo. Other significant figures included poets Nedjeljko Radić and Fra Ljubo Hrgić, as well as Dr. Abdul-Aziz Asko Borić, a physician, writer, and the mayor of Zenica (1932-1935). Zenica also had several sports clubs and societies, including the “Osman Đikić” club, “Građanski,” sports clubs “Željezara,” and “Džerzelez,” among others. During this period, population growth was significantly slower. According to the 1931 census, the city of Zenica had 9,078 inhabitants (4,086 or 36.2% Muslims, 3,243 or 24.3% Catholics, 1,399 or 18.2% Orthodox, 102 or 0.5% Protestants, etc.), while the Zenica district had 35,883 inhabitants.

In the brief April War, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was defeated, and by mid-April 1941, the 14th German armored unit entered Zenica without resistance. The Germans had both regular units and an intelligence service in Zenica throughout the occupation. With the support of the German military command, the Ustasha authorities and Home Guard units were soon organized in the city. The new authority promptly began persecuting the population, particularly Jews. Before the war, there were 172 Jews in Zenica, and only five survived the war, including the renowned Zenica doctor Adolf Goldberger. The partisan movement was active in Zenica and had many sympathizers, especially in the Tetovo and Gradišće regions, many of whom were tortured and killed in the Zenica Penitentiary and the former Sokol Hall. An interesting note from this period is the stay of Josip Broz Tito and partisan units in the village of Šerići near Zenica in August 1943. Zenica was liberated during the night between April 11 and 12, 1945, marking the end of a four-year occupation during which 346 partisan fighters and 857 civilians lost their lives.

With the creation of socialist Yugoslavia, a tumultuous period began in Zenica’s history, during which Zenica significantly expanded its territory, population, urban appearance, and acquired conditions for substantial cultural, educational, sports, and social development. According to the 1948 census, Zenica had 15,550 inhabitants (the district had 35,390), and by 1991, the Zenica municipality had 145,577 inhabitants (80,337 Muslims, 22,651 Croats, 22,992 Serbs, 15,651 Yugoslavs, and 4,306 others), illustrating its progress. Željezara Zenica remained the city’s main symbol, and during this period, due to numerous expansions, it became one of the largest in Europe. Other enterprises also progressed, and numerous new ones were established, some gaining significant reputation beyond Yugoslavia. Economic success led to a tremendous increase in the population, requiring new investments in urban infrastructure, construction of large residential blocks, expansion and improvement of the communal system, traffic development, etc., shaping the image of Zenica as a gray industrial city. However, this is not the true image of Zenica, as demonstrated by its cultural and sports achievements. The National Theatre in Zenica was founded in 1950 and soon gained broader regional importance as one of the crucial cultural centers in central Bosnia, further confirmed by the construction of a new, modern building in 1978. With the establishment of the Institute of Metallurgy in 1961 and the Faculty of Metallurgy the same year, along with the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering in 1967, Zenica had the opportunity to produce highly educated and skilled professionals, and importantly, retain them. Sports in Zenica have a long tradition, evident through numerous clubs in various sports and the significant number of people engaged in sports. Football has always been the primary sport in Zenica, and the seventies were the golden years for Zenica’s football when Čelik achieved notable European results, and a new, then most beautiful stadium was constructed, now serving as the venue for the Bosnian national football team. Other sports are also well represented, with rugby being a distinct feature of Zenica, present since the mid-seventies. Zenica’s rugby team is a multiple champion of Yugoslavia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and interestingly, the only national sports association based outside Sarajevo is rugby, with its headquarters in Zenica.

During the difficult times of the Bosnian War from 1992 to 1995, Zenica served as a sanctuary for many people affected by the war, primarily from central Bosnia but also from other regions. Zenica had a specific position and role during this period. It is lesser-known that the first currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina was printed in Zenica. The initial military reviews of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, attended by representatives of the highest military and political leadership, including President Alija Izetbegović, were held in Zenica. Amid the war, Zenica organized the ZEPS trade fair, which gradually became the most significant event of its kind in Bosnia and Herzegovina, evolving into one of the city’s most recognizable brands. The first domestic international football match of the Bosnian national team against Albania was played at Bilino Polje (the site of ban Kulin’s abjuration). After the war, Zenica continued to progress, gradually shedding the image of a gray industrial city, and emerged as a true sports center for all of Bosnia and Herzegovina.